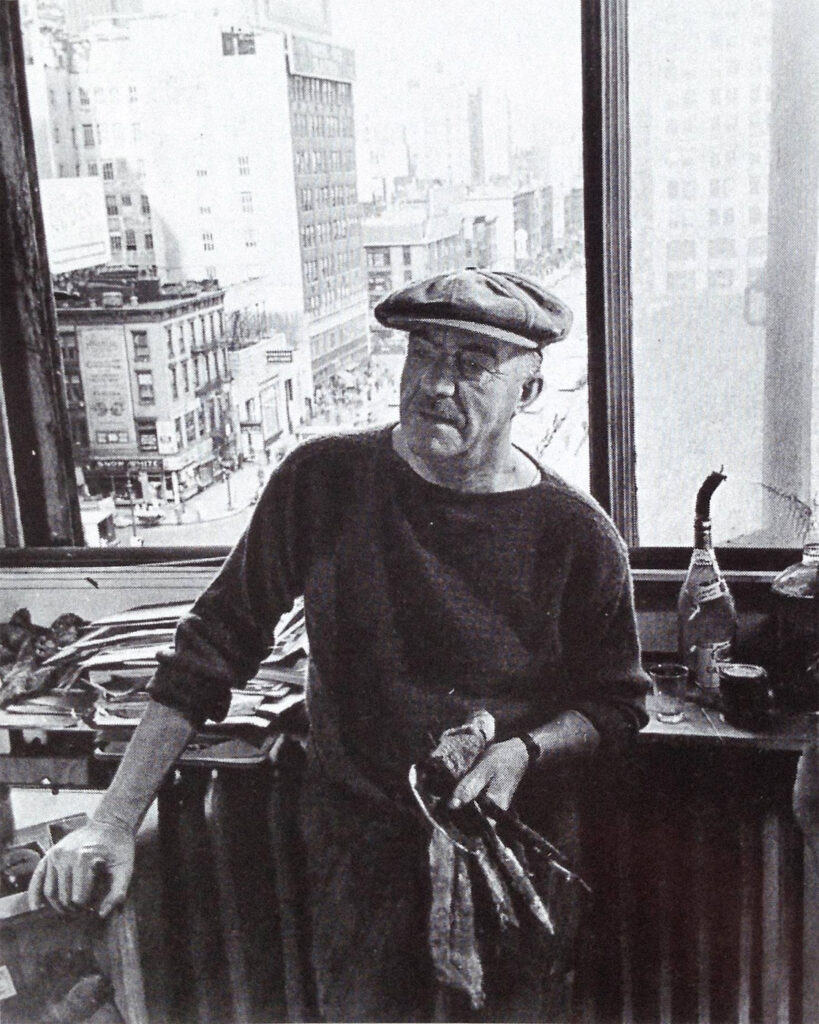

Oral history interview with Burgoyne Diller, 1965. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Interview by Harlan Phillips

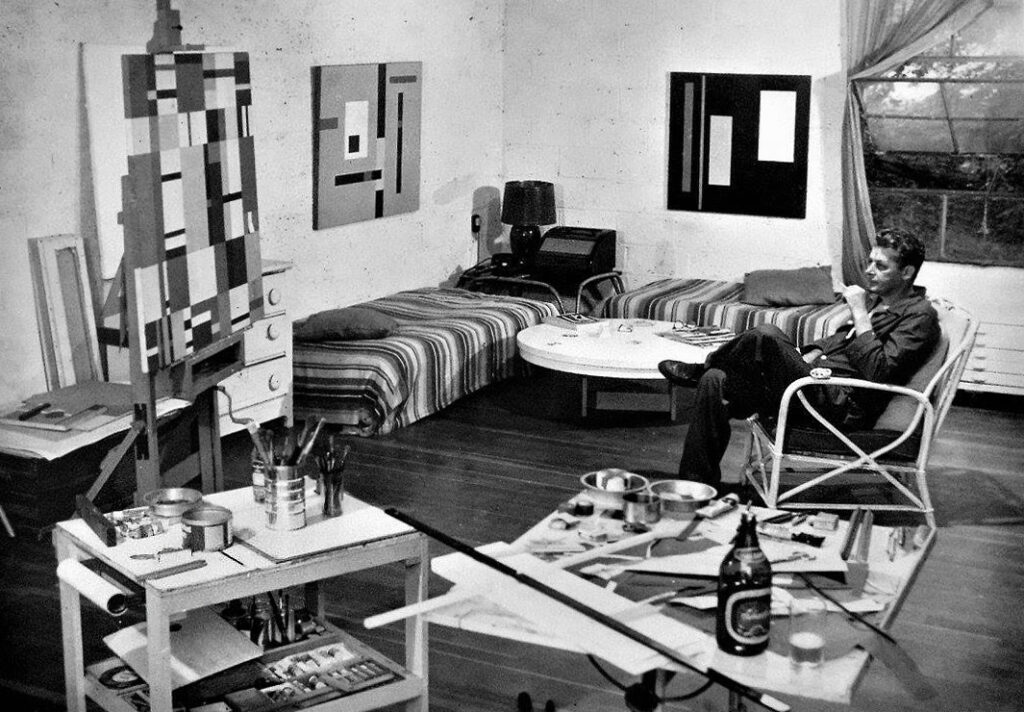

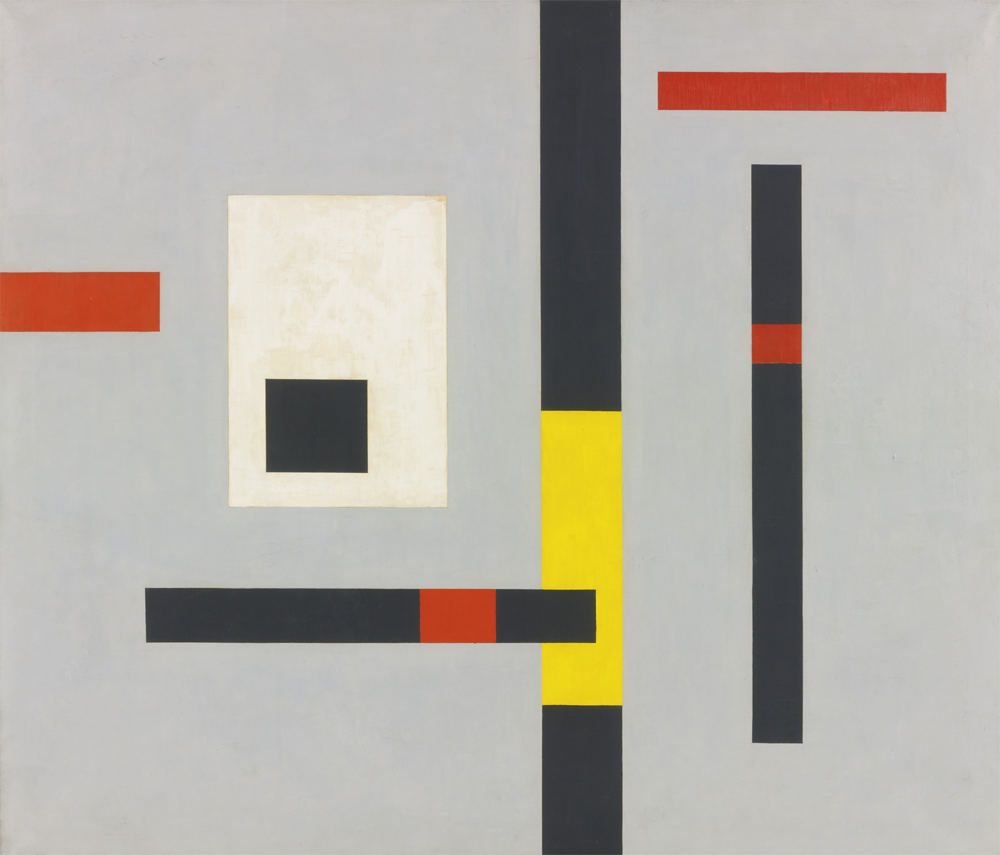

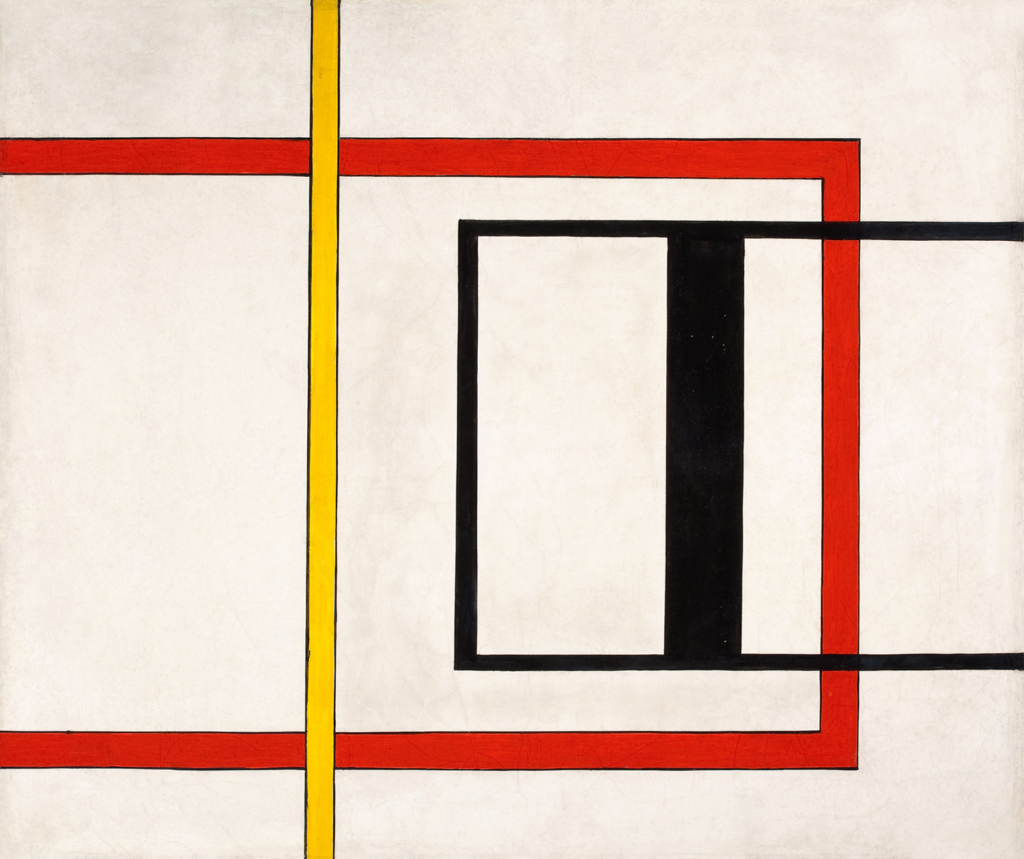

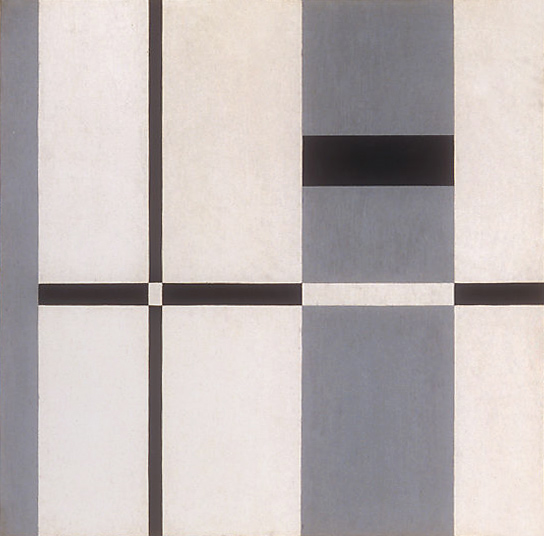

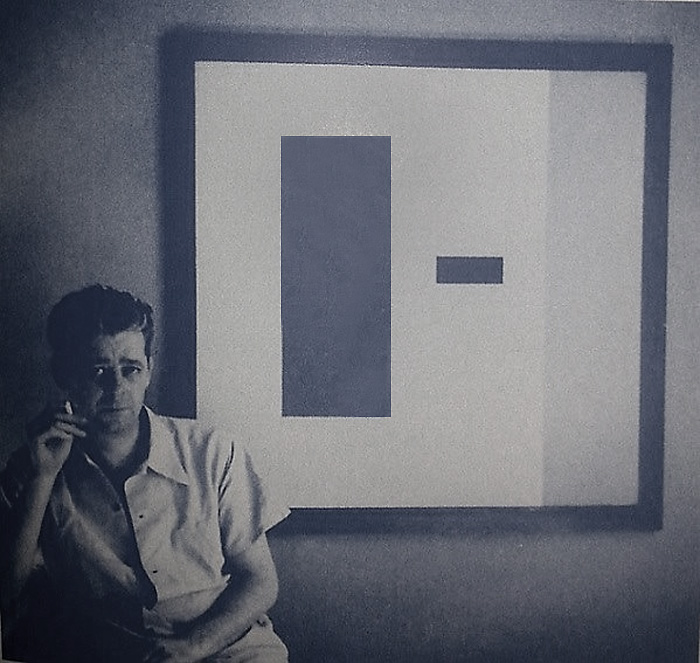

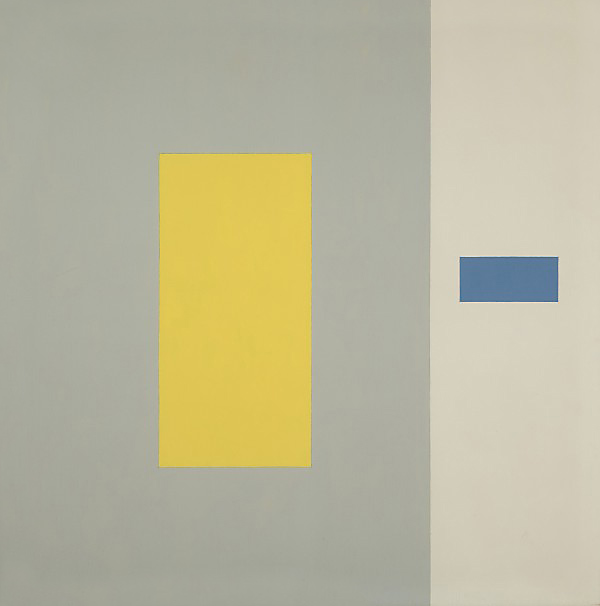

Burgoyne Diller was probably the first American artist to be influenced by the neo-plastic principles of Piet Mondrian. Prom 1928 to 1930, Diller studied at the Art Students’ League discovering cubism and the work of Kandinsky and Arp. It was not until 1930, however, after leav ing the League, that he began incorporat ing constructivist ideas into his work. By 1933, elements of De Stijl appeared, and in 1934 Diller produced a series of painted wood constructions. In 1934 and 1935 he painted Geometric Composition, a group of works that followed the grid work style of Mondrian and Van Does burg. These paintings were among the earliest investigations of those radical points of view in an America of social realists, American scene painters, and the rising tide of regionalism.

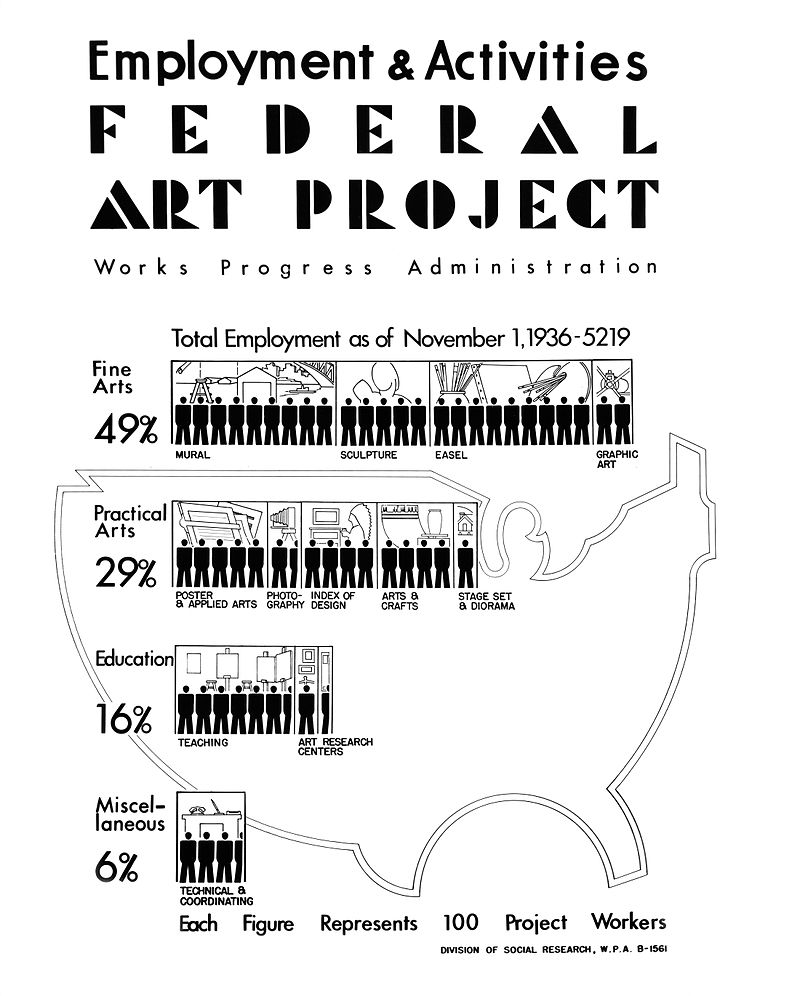

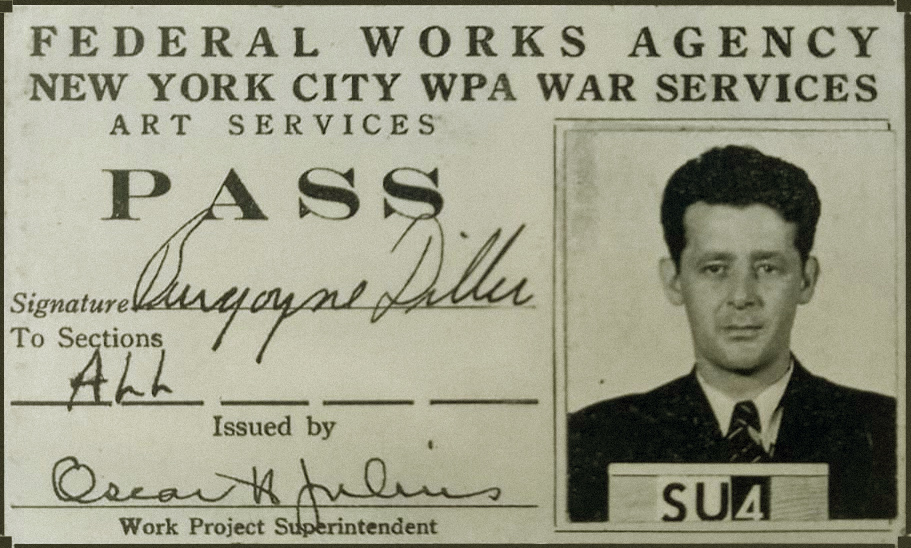

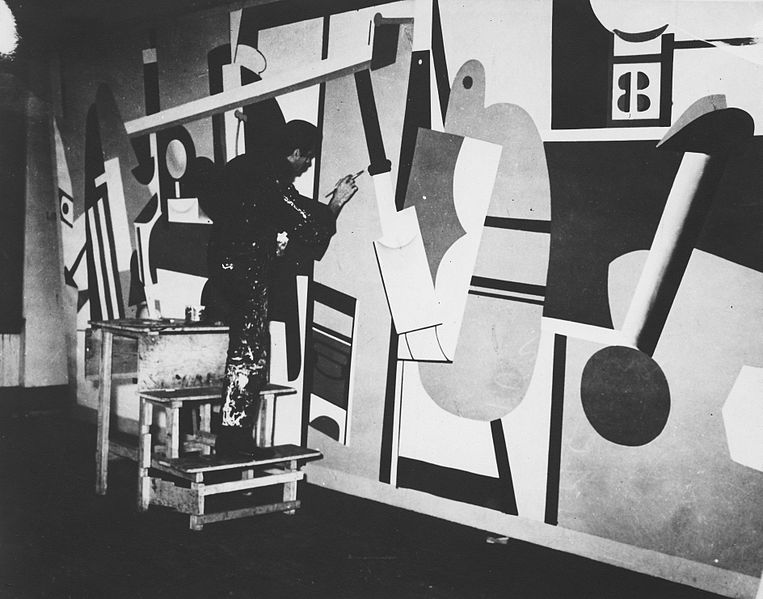

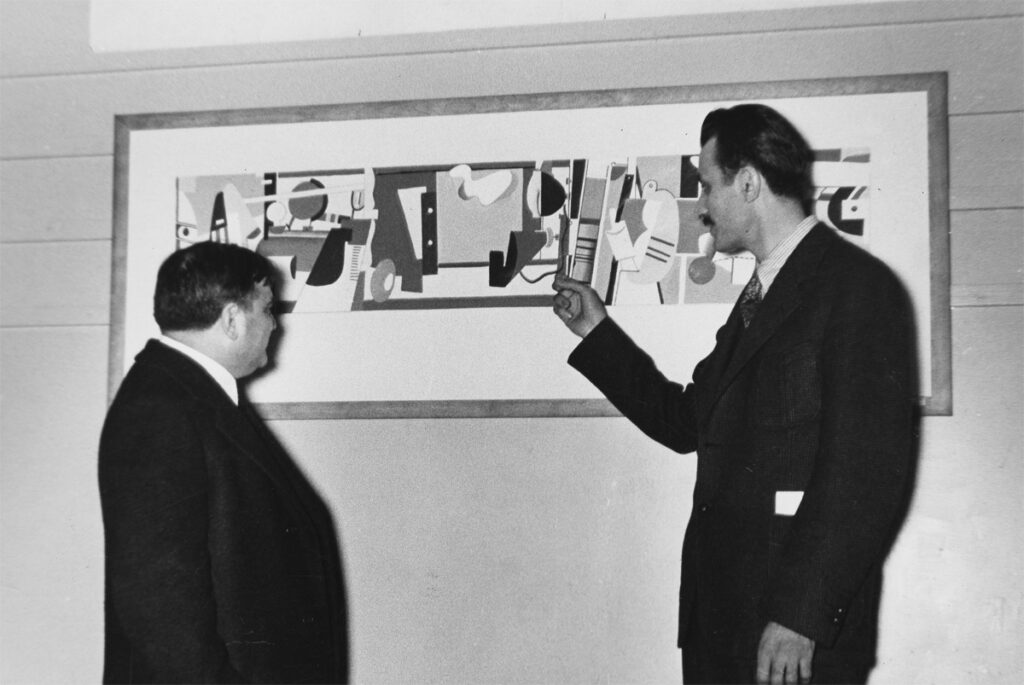

It could be argued that Diller’s greatest influence was not as a painter, but in his capacity as head of the Mural Division in the New York City section of the WPA. From 1935 to 1942, he was in a position, as the exponent of the most vanguard thinking, to successfully in sinuate into the general cultural murals by some of the leading modern artists of the time.

His ability not only to under stand the artist’s point of view, but to accommodate it to the needs of the political and govemmental figures of the time is evident in these interview Diller made with Professor Harlan Phillips of Columbia University, conducted for the Archives under a special program by the Ford Foundation to document the history of the WPA. In this discussion of October 1964, only a few months before Diller’s death in January 1965, he reminisces about the social aspects of the times, the art project, its administrators, political figures, and artists.

You know, this whole period of the WPA and more particularly the New York WPA is a kind of atmosphere that has to be recreated. In a way, it’s the circumstances under which what took place, took place. Now I don’t know – – as a point of departure before we get to you personally – – what do you remember about the atmosphere in New York as ’29 went into the ’30s, so far as the artists were concerned, and more particularly the modern artists? What the heck was life like – you know, opportunity like? Chance? Galleries? Interests? Market? Any of this strike a receptive chord?

Probably too many chords at the same time.

Well…

You name it. I mean, for instance, one thing that certainly characterized the period was lack of work, lack of money just to get the necessities of life. I mean, you learned to eat practically nothing so you could buy a tube of paint, and so on and so forth. You had a little part time job, or you’d pick up all sorts of crazy things in order to exist. It seemed to be true of all the artists. Whatever markets there had been prior to, probably 1928, ’27, I mean, seemed to be thoroughly dried up. The galleries – – there wasn’t the number of galleries we have today – – and if you happened to be concerned at all about the contemporary movements in art at the time, which then, of course, were Cubism and so on, why there was absolutely no place to show your work. Then, of course, you had the opposite of what you have today, to show representational painting. Then we had this problem again with abstract painting. Where would you show it? You were terribly fortunate to be shown any place, which is really, you know, the thing that brought the American Abstract Artists into being, so that cooperatively they might be able to finance a place to have a show once a year and that sort of thing. It was a very necessary thing.

Yes.

After all, your so-called big institutions that were supposed to have done so much for the artists, you know, in the past, the Museum of Modern Art, and so on – – I don’t think they had a prohibition against showing American abstract painters, but they didn’t show them. They showed very, very few of them.

Yes.

I know that the artists at that time, the abstract painters, they petitioned them to let the American Abstract Artists have a show there and so on, and they insisted that it would lower the Museum standards unless the Museum could select the work itself and present it as they wished to present it, which would being it back to the situation the American Abstract Artists already had, because they certainly had no choice then of anyplace to exhibit. I am confronted at the moment with the fact that they presented the work to a larger audience, and that is probably a functioning institution.

Was there – from what you’ve said, there wasn’t much in the way of interest in things American so far as the modern movement was concerned.

You mean in things or people?

In art in the ’20s and as it approached the ’30s what is it – the collector was interested in foreign things of a modern kind. Even the Modern Museum was interested in foreign works of a modern kind.

That’s right. And I think the prevalent thing at the time certainly was that if a person had money, they went to Europe to buy paintings.

Yes.

To such an extent that I know one artist in particular — you know, he married an American girl. He was selling very well, doing very interesting work and selling very well and most of his sales, however, were to Americans who went to Paris. He married an American girl. He went to Virginia to live, had a beautiful studio; said it was the most wonderful setup he ever had in his life to work, and he worked hard, but he never sold a painting during the time he was here. I saw him just before he was leaving to return to Europe, and he said that he just gave up, that he’d been here almost two years, had sold absolutely nothing. He said “Now if I go back, I know I will sell to Americans again.” He did. I received a card from him later on. He said, “As I told you, the Americans are buying my paintings again.” You can imagine what an American artist was doing who couldn’t retreat to Europe – his situation. I mean this prevailed. There was not only no financial interest, but there was even — such a scant interest in the work itself, aside from supporting it. As I said, you were very, very fortunate to show your work.

Yes, but I think, you know, this impulse – it goes away back, the desire on the part of the non-traditional artist to get together with other non-traditional artists to hold a show of their work partly because the dealers were not interested. The Brooklyn Museum, once in a while, would have a show of what were then called modern things, a Dana at Newark would have a show, Max Weber, for example, but Max Weber was what? Nothing in the ’20s – in terms of a market, or interest on the part of Americans for his work. Dana saw something in it. The fellow who was running the Brooklyn Museum catered to a developmental approach, you know.

What was his name? Yutes?

I believe so, although I…

I remember Yutes mainly as the person I think I knew in the ’30s there, and I think one of the things that he did as director, he protested against the 200 steps to go up into the entrance of the Museum, and he demanded that they remove the steps. After all, they had been placed there pretty much as a barrier to keep the common person from coming in and spoiling the works of art. He insisted that the stairs be taken away and an entrance made at the ground level so people could come in. He had faith.

Yes. But no more so than Dana, who insisted that the museum be right in the center of town, be part of the life of the place. Or his interest in collecting gadgets from the five-and-ten cent store, or glass that you could purchase, the common, ordinary things, and having shows of this kind of design which was within the knowledge, comprehension, appreciation of people. Not the catering to those who had an alleged taste in an Old Master, but the broad sweep of things. I suspect the modern movement was, you know, part of this broad sweep to encompass something American. I don’t know whether you got any pleasure out of the fact that the nation as a whole in ’29, and thereafter, ’30 and ’31, finally caught up with the position that the modern artist had been in all through the ’20s, when our economic system fell on its back. There was some problem about what to do in the way of projects. You can’t compete with industry. You have to find an area that is somehow, some way safe, you know, from competing with industry, so public buildings, like post offices, schools, courthouses and the like began to be talked about, because this is one way in which the government could convey both interest and create work. Somewhere along the line — and I don’t know how or why — well, there had been a series of things, the FERA, for example, but this wasn’t art for itself, and an artist in those days in the FERA could be employed in almost any way, whether it was road building, you know, they didn’t make a distinction. Then I suspect people like Baker and others saw a way to alter FERA to include CWA, the Civil Works Administration, which included within it some opportunity for artists under Edward Bruce, I believe, the Public Works of Art Project. All by way of background as to, you know, where does that artist fit in society when he’s hungry, and since society is on its back, what can we do. Well, in a way this is a funding problem. In New York itself there was a thing called, I think, the Gibson Committee, do you remember it?

That’s right. They set up a committee exactly for the New York City area, and it was aimed toward the employment of artists.

Yes.

And it didn’t go on too long, but I mean at least it was starting something.

It was a seed.

But the remnants of that were picked up by, I think it was, TRAP.

Yes.

The Whitney Museum was the center from which — the Whitney and their associated directors and the other people they selected acted as the committee to pass on work. That was an extraordinary thing in the sense that the artists selected by them were given a schedule for working in their own studios based on the artist’s own production. In other words, if the artist said, “Well I spend three months painting a painting,” or six months or whatever, and it was a reasonable statement, they’d accept this as the time schedule for him to bring in a work. Now at that time there were very few abstract painters. I happened to be one of the abstract painters that were in that group, the original group. I think Gorky and Stuart Davis and I’m not sure who else, but there were not very many at the time. Then that of course went out of existence.

Sure.

The only thing carried on from that was a series of mural competitions that they started for buildings in the City of New York. It was – the painter’s name was Eric Most. He had won one of the awards for the Roberts High School. I’d been dropped from the project as others, the other easel painters had, for some period of time. Then I was invited to work with him to act as an assistant or whatever, to help him with the mural. But because they had received funds, I believe they were funds, that were either carried for them to complete these mural jobs, or nearly complete these mural jobs, which was later taken up by the beginning of the Art Project as such and finished, terminated. So that I was working with him when the larger program started under WPA or rather, pardon me, the Federal Art Program.

Yes.

Then I was moved from there to the Federal Art Program at the initiation of that when they first started building it up, you know, when it first really got going. I went there as a mural supervisor.

Yes. I wondered, you know, and again by way of seeds and background and aid, what function and role did the College Art Association play with reference to local artists? Any at all?

Well, the College Art Association had been, through Mrs. Audrey McMahon, I think, mainly, had been tremendously interested in the potentiality of these either city, state, or federally-operated programs assisting the artists.

Yes.

Because the problem of unemployment, you see of artists as such would be brought very sharply to their attention because so many of the colleges throughout the country employed the few artists that were employed, you see, as art historians, or whatever. The College Art Association had always maintained an employment bureau for art historians and art teachers and so on. They had a magazine which heralded the possibility. I think they did a great deal. The Association really was an important factor particularly when unemployed artists came to Federal attention and because, as I said, the Federal Art Program. The first offices were at the College Art Association.

And it did, I think, several things – Mrs. McMahon, whose interest is long and deep in the field, plus the fact that the lack of a place to show one’s work encouraged the College Art Association also to have shows where people could show their work, or to support shows.

They organized circulating exhibitions that went around the country. I know that in that early period I had been invited one time to select the work for a very modern sort of show of the Constructivist painters and the style and so on, which was organized later and sent around as a circulating exhibition. They really did try to bring to the general attention the work of contemporaries.

Yes. What about the Whitney Museum and more particularly Mrs. Force, who was, I guess as the name implies, its driving force?

She was. I was never really acquainted with her. Naturally I met her, but my contact with her was very slight, although I did know, as any other artist who had been around New York knew, that she was the one that really was the motivating force toward a great deal of our activities, probably activities that are culminating now in the growth they have experienced.

But isn’t this another source of interest in what was called in the 20s the modern art movement?

I think the Whitney Museum at that time was not as concerned about the — there again, you have to draw a line about what you mean, “contemporary art,” and “modern art,” “abstract painting” and so on. The Whitney was, I think, more concerned with what they would call the American artists. Now that might be in the more familiar terms of the American scene painter, or probably partially socially-aware artist of the time who was talking, you know, making statements and so on. But mostly, I believe, the American Scene painter. I think if you were to look back in the catalogues of that period, you would recognize some fine painters. I mean Hopper and heaven knows who else, that have done rather outstanding things. But there was a very slight encouragement there of abstract painting, or anything of the sort. Stuart Davis was there, you know, included always because I think probably it was his good fortune to be with Mrs. Halpert and the fact that the group that she had was the group that was very much appreciated by the people at the Whitney.

Yes.

And therefore Stuart was more or less included with them. Then too, Stuart Davis always did have a little signature of the American Scene, you know, a work or a gas tank or something of that sort, so it made him more acceptable in a sense.

What you’re saying then is that the Whitney was more selective in its support, or its encouragement than the College Art Association would be?

I think the College Art Association had a more general educational viewpoint of work and probably a more objective viewpoint, while the Whitney Museum, as you said, had a more selective viewpoint because it was considered the American museum, and they were trying to more or less build that up as strongly as they could. But the attitude toward what was American was a pretty sharply defined line. As I said, I think you could express it best by saying the American Scene sort of painting.

Yes. When the Federal — the WPA I think was announced in June, the latter part of June in the summer of ’35. Hopkins…

The WPA, now are you referring to all the Federal Art Program?

I’m thinking of the WPA and within it the Federal Art Program Number 1, which is the subject really of our interest, but Hopkins was present in New York and the names of the people who were going to head up the four projects were announced in the press with certain regional directors allegedly chosen throughout the country. For example, the announcement of Eddie Cahill for the arts, for the subsection Federal Art Project Number One, and then there was Henry Alsberg and…

Hallie Flanagan.

Hallie Flanagan and Sokolov in music, so that suddenly — I say “suddenly,” but the Gibson Committee, to some extent the Whitney, the College Art Association and various state and city projects had already indicated some need in the arts, in the creative arts. Nonetheless, this is like a front page indication that the Federal government had discovered that “artists” including musicians, writers, actors, actresses, artists were also to be aided in the sense of a project. It wasn’t entirely clear the nature of the project. How did you first become aware of the existence of this? You have indicated, I think, that you were on something which seemed to have continuity in itself, and they just changed sort of headings.

That’s right, as I said, I was on the TRAP. After a lapse of a few months, I was asked to be an assistant to Eric Most on the mural, which was a carryover, and then that was picked up for completion by the beginning of the Federal Art Program. But in the meantime, I was asked to work in the office as a supervisor, so it was a rather continuous thing.

Yes. How did — well, you know, had you given thought, or was there discussion among artist friends of yours as to the nature of this new WPA, or no?

I think that in a way there had been a lot of discussion. Particularly the artists had started organizing in order to demand assistance. Mainly at the time for the city and so on, and there was also the feeling that the State should enter into it and then finally suddenly that the Federal Government should enter into it, so it was something just building up, something that hadn’t reached any kind of maturity in its demand, but still the demand was there, and it was vocal.

Yes. I think this is a feature that’s often overlooked, namely: that artists, for example, who can be as ruggedly individualistic as any creatures in the United States were finding somehow through union organization a collective power which each individual artist could not exercise. Starting with the City, the Artists union marches on City Hall, the effort to get a local art gallery operating and you know, functioning under artists themselves, this kind of thing — like having a vested interest in breathing and making it substantial through organization of other like-minded people, as a collective force, but heck, collectivity was in the nation as a whole as something new, unionization of the automobile industry and the steel industry was going on at the same time, so collective organization must have been in the air.

Collective seems to be a term of accomplishment in a sense. Actually, I think that what happened was for the first time there was an association of artists, and by that I mean mutual association because of mutual needs. For the first time artists were talking together in large groups so that there was a possibility for arriving at opinions that were mutually heard. And God knows there are differences of opinion, but on the whole they were united by one very simple, basic thing. They needed to eat. Don’t forget those times were not — you’re not thinking of art as much. Of course, the artist always did. He’d probably starve to death still wanting to paint a picture, but on the other hand, your primary concern was how do you feed yourself, how do you feed your family, and the artist was possibly in some senses considered the least employable, perhaps because of their eccentricities, or whatever you want to call the name for it. As a matter of fact, I found during that period that the artist was probably the most self-reliant, self-sufficient individual in the City of New York. You had some of your top-management people standing on a corner selling apples, but somehow or other artist had so many accomplishments, craft accomplishments and related things that he could do, that he somehow or other survived. However, this did not keep the total specter of the wolf from the door, you know.

Sure.

The next day what are you going to eat and how do you buy a tube of paint? All right. They all have this need. They get together and they talk about it, and if they talk about that, they can’t help themselves because they’re made that way, they also talk about art. Then they start having battles about art, and at that time, you know, the terrific thing was that on one hand you had a strong development of the social scene painter, you know, “If you’re painting abstractions, you’re painting in an ivory tower” and, you know, “You’re not relating yourself to society.” Your abstract painter was saying “Well, of course, if you’re just a social-scene painter, you’re just another medium of communication but a bad painting probably,” and so on. Do you know that’s the first time in history that artists in these numbers ever came together?

Yes.

If before in any period artists came together, they came together out of one culture, one tradition, in Greece, or wherever it might have been, but there you had people from all over the world representing every culture, representing every viewpoint and united on the basis of art.

Yes. I think that’s a feature of the period, you know, which is often overlooked. For example, there have been — oh, in the past, 1910, 1895 — a group of artists who disagreed, you know, with the dominant group of artists who were picking shows, or put on juries and so on, and they delivered a kind of manifesto of deviation from them and, you know, these are important names in American art. There was a question of aesthetics. “I’m not getting a good hearing on my work,” this kind of thing. But here in the 30s, it’s a wholly different kind of proposition. It’s the identification of an artist as also a human being in an industrial society and seemingly no place, no niche in it for him…

And he was firmly convinced that the work he did had a place in society.

Right.

Was important to society, was important to the cultural development of America, but he’s the last one that society would think of supporting unless he happened to be a mechanic who would do what they wanted him to do…

Yes.

If he’s a good decorator, or if he’s a good illustrator, or painted what they thought to dictate was good art then they could use — and I mean probably literally use him, but the painter felt he had a more important, more basic social and cultural relationship than this, and he felt he had as much right certainly to work, to produce his work as a ditch digger did that had to dig a ditch….

Right.

Even if he couldn’t get as much pay for doing it.

But how are we — you know, this gathering of these individualistic, creative, aesthetic people – artists, this is a gradual thing, an assertion, this common voice, or talking about a common problem impelled by a need, or the discovery that one had an empty stomach, that it had been empty all through the 20s, in effect. Although, you know, something else you said strikes a chord because in talking with Davis, as an example, all during the 20s while his art didn’t sell in the sense that selling is, somehow, somewhere some persons, some group of people, somehow he was able to keep going, namely on whatever it was that attracted his insight that he wanted to do, the main line of his own thinking and expression and development.

In other words, somebody would buy a painting, or he’d have a teaching job, or something would come along that would keep him and sustain him.

Yes.

This was true of most of the painters of, let’s say, his caliber. I mean like Gorky. I never knew of Gorky working at a laboring job. Gorky always said there was someone who wanted to study with him who could pay him a little bit, and he taught at the Grand Central School of Art. He had a class there and, as I said, just had a person here and there that really thought his work was outstanding and worth investing in, of course, investment was so little at the time, but it was enough to pay the rent once in a while and keep far enough ahead and eat and maybe even have a drink once in a while…

Yes. But then when the nation as a whole collapsed the possibilities of sustaining oneself grew less and less, I gather…

Oh, certainly…

So that hunger propelled a group to develop as distinct from an individual like Gorky or Davis. You know, instead of themselves being able to keep themselves sustained, they confronted a kind of emptiness as everybody was shot, everybody finally joined the artists in wondering as to what tomorrow was going to bring…

Not only wondering about what tomorrow was going to bring, but realizing full well when you got up in the morning, “How am I going to feed my family during the day?” It was a very stark and very real problem and I think that other artists probably had the experience that I did — you know, getting out of college back in ’27, the end of ’27, this period of decline really started. I was in the Midwest, but it was this sort of thing, I went to Buffalo and I got a job. I was there for probably two weeks, and they laid off a hundred people, and I naturally. I was the last taken on. I got a job trimming windows, and they dropped half the crew after I was there three weeks. I got a job in a silk screen place, and again I lasted a few weeks, and then they cut back the force. It was like snowballing down the hill. Finally, just by sheer pull, political pull — you can believe this or not — I got a job as a porter in the Buffalo post office. You know what that meant; that meant swabbing the decks and shoveling coal, washing windows, and the only reason I didn’t clean the latrines was because – well, you have partners, and my partner was afraid to do windows on the outside and so he cleaned the latrines while I did the windows on the outside. But this is typical of the artist. I landed in New York City. I wanted to go to the Leagues. I had no money, but I did get a scholarship to the League. What did I do? I went to the little restaurants and painted signs for them in exchange for meals. You went through such a variety of funny, ingenuous ways of trying to live.

In short, you, like many of the others, had a preparation for survival through the multiplicity of things that you turned your hand to of necessity.

And frankly any other artists I knew had to do the same thing so the result is we became multi-talented. The dangerous thing of course — jack of all trades and master of none. In other words, our mastery of one, the one we wanted, was rather elusive, because how could you spend time doing it when you had to spend time getting enough to survive …

Just to survive…

I thought I was terribly fortunate because I had a scholarship. Then I got a scholarship job at the League, and I sold paints in the little store for a few years there. It was only an afternoon job but, you know, that was money. It wasn’t much, but believe me, it was a lot compared to most of the artists that I was friendly with at the time. So it was a question of most of us just pitching in together, and sometimes we’d have one pot of soup for ten. Sometimes hardly enough for one. It’s crazy, but it was wonderful.

Yes. But the…

I think, as a matter of fact, there’s something that’s unforgettable about that period. There was a wonderful sense of belonging to something, even if it was an underprivileged and downhearted time. You just weren’t a stranger. Now we’ve reverted back again to the days when the artists rarely meet. If they do, it’s under such artificial circumstances, and they’re so infested with hangers-on, and it becomes, you know, a battle of cliches. Everything else in the world except the very vital, fundamental issues that you were confronted with then that made you sleep together…

A complete change.

Because then it was a matter of survival, but, as I say, it was exciting. I cannot look back on it and say, “here, this was a time of pain.” God knows, there were problems, there was unhappiness, there were many things, but underlying it was something that maybe in a sense you lose contact with in such a false environment as the city, or a farmer might have in the farm, his attachment to the soil and things that grow, that sort of thing — I think something kind of rather fundamental, and somehow or other you were aware of it. We were all aware of it. Our differences between ourselves aesthetically — well, they degenerated into a kind of quibble unless they were being utilized for political reasons. In other words, you could be a very academic painter. I could be a very abstract painter. We could get along fine. The only time we had a pitched battle was if you decided that painting had to be directed only towards the Marxian function of propaganda, or something of the sort, and I had the unholy attitude of art for art’s sake, you know. Then of course we’d become terribly involved. This is what happened in the Artist’s Union, the Artist’s Congress, those organizations, but as I said, there was such a basic thing to hold them that no matter how much they would quarrel with each other, they still had to hold together, or else they’d be lost…

Yes. Well is there an ingredient in this coming together, the fact that they had a common employer, the Government. How did they look upon that?

I think that the coming together started before the government stepped in because I still remember hanging paintings on the fence in Washington Square when men like Vernon Porter and some others organized — they got the City’s permission for the artists to sell works on Washington Square. Now that was the beginning of these Washington Square shows, but believe me, at that time you had all the name artists hanging their wares on Washington Square and hoping against hope, you know, that they’d sell anything for anything, any price…

Yes.

And as I said, there you had the beginning of a kind of cooperative spirit and the necessity for cooperation before your projects came into existence. I think your first sign of it was actually in the Washington Square shows. Then afterwards the committee from the Washington Square shows — well, I remember one name more distinctly, Vernon Porter, but there were others. Then rather than just drop it at that point, you see, they’d go to restaurants and to hotels and theaters and try to organize shows for artists because they had a long list of them, you know, that had hung at the Washington Square show. Every once in a while, you know, you’d get a little note asking if you wanted to show in the Roxy, because they were able to show fifty canvasses up there for a week, or two weeks, or in a little restaurant down in the Village, you know, or in a restaurant up town, and so on. This was something that really worked, and I think it was one of the things that again was a strong motivating force in bringing into existence the concept of a government, city, state or federal that recognized not only need, but the necessity to provide some form of work, or at least space to show, or some way for the artist to survive.

Yes. So that these more formal organizations, like the Artists Union, and the Artists Congress were extensions of this. The scene changed too, but extensions of this early coming together, identification of interest and need.

Yes, as they became more formalized in their demands and also in the possibilities of that sort of assistance.

Yes. That is, as the direction pointed toward government as the source of funds, you know, to sustain artists, it meant a more formal organization to — well, you know, rates of pay, sick leaves, etc, etc, etc, etc, etc. where unionization was a kind of feeling that was abroad in the land anyway — well, from ’32 on. Up until that time you know, unionization was looked upon as something to war against. Actually it wasn’t decided that you could really join something fruitfully until about 1936, when the Supreme Court said you could do it, you know.

Yes. Before that you were either a Communist, or IWW, or something of the sort.

Well, whatever the organization was, you were a whole host of other things except what…

Improper.

Of course, because it was a thorn that had to be dealt with. But what were the circumstances where you were asked to become part of the office force of the organization? What was the felt need? How was the federal art program organized so that they could see the necessity for supervisory assistance?

Apparently, New York City had been voted a certain amount, or rather, granted a certain amount of money. A certain budgetary limitation was set up, but the funds would become available. Now understand, this means money to be spent. Therefore, you had to have people working to earn that money, and this comes to putting people to work. When I was called in there, it was an extraordinary situation because the thing had been just started in that past month or so, and what we were doing — our job was to put people to work. But we had a doublefold responsibility. You can’t put people to work at nothing. The only thing you could do immediately was to say, “Well here, try experimenting with some mural ideas,” if you felt the man was capable of this work. You see, the work was submitted to a committee, and it was decided whether he could be an easel painter. Now that’s easy. We all can paint, you see. Or a sculptor, you know — “go off and prepare some sketches for a sculpture.” You could put them to work immediately, but in a division like the mural division or architectural sculpture, it was a different thing, because we had to get the sponsorship of public institutions in order to assign anything. Those people we felt were more immediately able to start developing projects we assigned to just general thinking about the things, about the mural, because don’t forget, very few men had had the opportunity of working on walls. We felt that if they just exercised a little bit until we could find them a sponsor, you see, why we’d be that much up on the game. I know that in my case it was a question of spending half the day, you know, on the committee, accepting the artists, enrolling them and assigning them to what I thought was reasonable that would help in the total picture that was developing. Then the other half or more of your time was spent in going out to city agencies and talking with people in public libraries and so on and having them request a mural. Now the commitment at the time on their part was really that they would have the mural.

They could order a mural through the head of the department, through their agency and, as in the high school, for instance, if they were a grade school or a high school, or whatever, you’d have to go through the Board of Education and have the Board of Education make the request. But the original request came from the school itself. So we’d have to talk to the school principals and so on and say, “Well here, we’ve looked at your building, and we think there’s an opportunity of having a mural in the auditorium, or in the hallways or something. It might be appropriate, and if you’d be interested and if they were, why we’d develop it from there. As fast as we could get these institutions committed to the sponsorship, then we could assign artists to make tentative sketches for the job. It was a problem really of, as I said — we had to have men at work in order to use the money that had been designated for the area and for the activity. If you didn’t have it, of course, the funds would probably be withdrawn. It was an impossible sort of task, but one that you thought you had to do something about. I think that in most cases it wasn’t too difficult to secure sponsorship of high schools and libraries. I mean it took some considerable amount of talking perhaps and so on, but once they realized that this was something that was within their own discretionary powers, and that the work would be subject to their complete approval, they didn’t feel too great a hesitancy about ordering, or becoming sponsors. I think the greatest threat to their acceptance would have been that work could have been put in there over their own decision of what they wanted. This couldn’t be. By the way, this was a tremendous source of newspaper comment. You know the headlines in papers like the Journal-American and other papers, particularly the Journal-American, was anti-New Deal and so on, but you know these murals were being rammed down the public’s throat and a communist mural had been torn down off the wall because it had these Red symbols in it and so on and so on. This was foisted down the taxpayer’s throat and so on and so on. As a matter of fact, it didn’t happen. It was silly because the thing that they charged was the Red Star of the Soviet Republic was the rear end of a Shell Gas truck that had a red star on it, you know the gas station has …

Yes.

I mean it turned out more or less like that. But you see, we could never get equal publicity for facts such as the method for getting a mural into a high school in terms of who approved it, and how little chance you’d have of ramming anything down their throat. The only thing that you could possibly do was probably get a better artist to do the job than they might have selected…

Right.

A man who had some formal concern with the work and really had something to give other than just the picture, the scene, or whatever. I’m expressing it in very silly terms, perhaps but, let me give you an instance of one of the high schools that the statement had been made that this was a mural rammed down their throats, you know, and so on. The principal requested a mural. They requested a mural. There was a regular form made up. He passed that on to the Board of Architects. They would only approve — this is of the school system — they would approve it only in architectural terms within these architectural limitations. It was then passed to the Board of Superintendents of the New York City school system. If they approved — this was only preliminary sketches — they were passed on to the Board of Education. Now if the Board of Education approved, it was then submitted to the New York City Art Commission. If the New York City Art Commission approved, it was given preliminary approval, which meant you had permission to start work. The work would have to be viewed by the New York City Art Commissioner periodically to make certain that it was the same thing as presented in the original sketch form. Now when the mural was completed, you still had no right to the mural because when the mural was completed, the principal had to make out another form requesting final approval of the mural. It then went to the Board of Architects for their final approval. It then went to the Board of Superintendents for their approval. It then went to the Board of Education for their approval. It then went back to the New York City Art Commission for their final approval and the mural was in. Now if through that barricade you could ram an idea, or anything else in there, down the throats of the innocent taxpaying public, I’d like to know how the hell it could be done!

There are more checks and balances in that process than there are in our Federal system. I gather that, you know, in finding wall space as in a school, I would assume that one of your tasks would be to actually find wall space, to survey it…

That’s right.

As to whether it would or would not be adaptable to a task at which you might employ an artist.

That’s right. You had the first task of actually seeing whether the wall space really made sense, whether there was any rhyme or reason for decoration being there. Then of course you had to select the artist that you thought would be most competent to execute the work. And it couldn’t be made into a competitive thing, as TRAP, for instance, as our post office murals were, you know on a competition basis because this thing had to move along once you got started, and there were so many possible jobs that it wasn’t like the post offices were, where there’d be one in a whole region and maybe a hundred artists competing for it, you see what I mean?

Sure.

There were plenty of available spaces. Now I don’t mean it was easy to convince these people that they should have a mural, or whatever, I mean, some of them of course wanted to have hearing after hearing to discuss it, and then they’d have to cover themselves. They had within their own family, you know, they’d have their Art Chairman and some of the other people in the school, you know, go into lengthy debates about the subject matter and so on and so on. By the time we got the sponsorship sometimes there could be quite a delay. This meant that you had to hit five places to make sure you’d have one next week to assign to an artist. Then as fast as you could assign the artists, then you could assign the assistant, start assigning assistants, probably one first just to help the artist gather data. Most of the murals involved subject matter that needed research and so on. They could start doing research, and whatever, and then a little later, why you might assign more if it were a large job, you know, because then you have the actual job of setting up big wall space.

Yes. But, you know, the draft, the original drawing…

Yes…

This was on the basis of research?

It was on the basis of an artist being given the subject matter by the school and doing as much research as possible — I mean by that doing a thorough job of research and then we presenting that to the principal of the school again to make sure this was a thoughtful statement of the thing the principal wanted done. In other words, the scene below, whatever it was. So the result is it called for quite a bit of consultation between the artist and the principal before it started out on that long siege of approvals.

Sure.

And most of the principals were cooperative; not only cooperative, but some went to great lengths to aid in the research because in some subjects it was rather difficult. They asked some of their teachers, you know, specialists who’d be more specialized in fields, to assist and so on. On the whole, the sponsors were really quite cooperative, but you see these — the majority, as I said — but this isn’t the kind of thing that makes news.

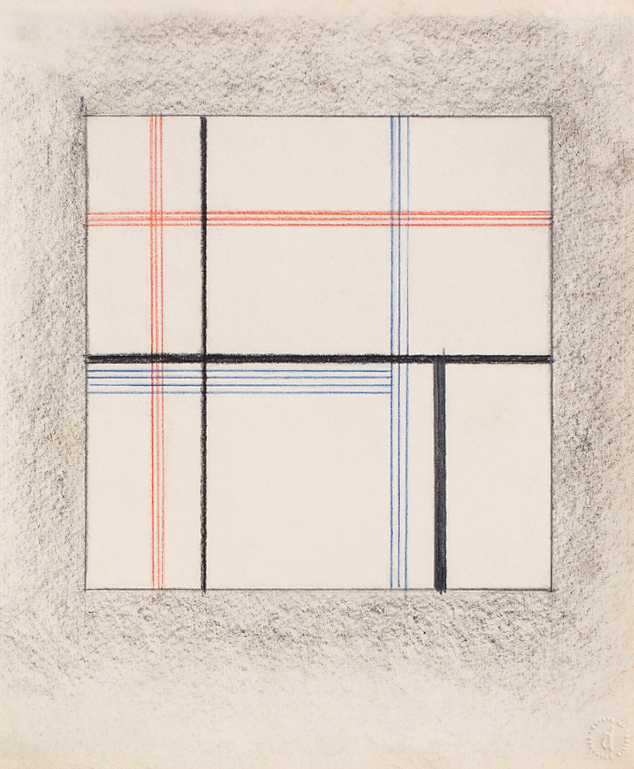

Graphite and crayon on paper, 22.5×19.7cm.

It’s always the…

The thing that makes news is the one who uncovered the fact that a mural being done in the music room of this high school was done by a young woman who had worked on a mural with Diego Rivera, and when they found that out, that, as far as they were concerned, made her a Communist. It was a fresco. It was half-finished, and it was torn down by orders of the principal. Now he had no authority to do this because he should have gone to the New York City Art Commission, and it should have gone back through the process, because in the mural itself, the girl had taken ancient musical instruments and painted a frieze around the music room. Even then no one claimed that there was one iota of leftist or any other kind of commentary, or any kind of commentary, except it might have been an improvisation built up on musical instruments. No charge was made like that at all, but he had found out through “a good soul” that this girl had worked on a mural with Diego Rivera. Now she had worked with him, I know, because she was concerned with the fresco process and most of the frescos, all frescos being done, most of them anyway, were being done in Mexico where there was a sort of renaissance of fresco painting. She had deliberately gone down to try to work with Diego Rivera because he was doing frescos, and she could actually work on the job. What her political viewpoints were, I have no idea. All I know is she was doing a job for us, and there wasn’t one iota of anything there that the most reactionary person could possibly protest as far as the motif of the thing, or the coloring, or anything at all. These are the things that you read about. You didn’t read about the other hundred jobs. We had 125 going on at one time, but you read about this on the front page, but not of the other 124. You know it was very unfair. You know you said — when I started talking about approvals and so on — originally you made a statement, you know, about what happened at that period, you know, where this thing was growing. Well, it was like a mushroom. We worked day and night and weekends and, believe me, we were not well-paid for it, but we thought it was the most wonderful thing that could be happening. We were enthusiastic and were ready and willing to do anything. It was a madhouse. I had somebody sent to me to act as a supervisor and, as it happened, he was rather elderly. He came and he said, “Mr. Diller, I was sent to you to possibly act as a supervisor. I’m So-and-so and I’ve had, you know, certain background.” He started to talk about that, and I said, “Oh, you did! That’s fine. The only thing I’m concerned with: See that desk. We have no secretaries. We have no typists. We just have bare desks with stacks of paper on them three feet high.” You know, everything was out – that was our file for the time being. And so I said to him, “Look at that desk. If you can’t find something to do, I don’t need you; but if you can, I love you.” He went over and got to work. Afterwards he told someone else that he thought it was so wonderful, that I was a young man and he was an elderly man, and he had gone there terribly frightened just because of his age that he’d probably be relegated to the wastebasket, you know, and he wound up useful, and he said it was so wonderful you know that I made that statement. All I could think of was “Wonderful, hell! I needed help desperately. I was drowning in papers and people.” I told you it was wonderfully exciting time.

Tell me this. How much direction, if I can use the word, did you receive from Washington?

Well, we had fairly regular visits from Eddie Cahill. They were more or less non-directive directives. I think they were things that had to do with the budget, number employed, and that sort of thing, and he bore the brunt every time he came to town. The Artists Union and the Artists Congress were laying in wait for him to clobber him, you know, about more jobs and more money and so on and so on. But as far as the work was concerned, I think that the only thing I felt constrained by — I was personally very much interested in abstract painting and so on. They felt that there was no place for it at the time because they felt that the project should be a popular problem and, while they didn’t attempt to invalidate, or question the validity of the work at the time abstract art had no place, because in a way you did have a great problem of building up public sympathy and understanding and a demand on the part of the public for the work. But outside of that — and conversations that you’d have, you know, when you’d get together, probably after your meetings, which were, as I said, more budgetary than anything else, probably you’d get together and you’d have a drink or two and talk. At that time it was probably, on his part, a recital of some of the things that were being done in the rest of the country. Some things he was more enthusiastic about than other things. But then we had our opinion. We might probably differ with him very much and we told him so, and there was no problem.

Well, the process you…

When I started assigning abstract things, and we had a number of very representational works, I felt certainly these people should have a voice, too. It was more difficult getting it, but I mean if I had ten jobs going, I could afford to start one that might be aesthetically a little questionable to some people. And on the other hand, you could say that while Cahill didn’t greet them with any degree of enthusiasm because he was still primarily concerned with creating a demand for the project on a more general basis, on the other hand, I say I survived. He never hit me. He didn’t fire me.

No. But the process you describe whereby one got acceptance of a mural would tend to preclude interference or direction from Washington. You had to negotiate with the principal to begin with…

That’s right.

And so other than saying that you might have told him this story, or taken this point of view, it’s inconceivable that Cahill, you know, would have an opinion except an over-all effort to get it accepted with public support, but the detail of whatever was worked out had to be worked out by you, it would seem to me.

If he had preferred to steer the thing completely, I think he would have been in an impossible situation, as you say, because it was beyond him, as it was beyond us to do something we might have preferred. In the case of Cahill, he was much too intelligent, however, to not recognize this fact, and I’m sure that when he talked very enthusiastically about some of the painters — well, I remember some of the ones he was very, very enthusiastic about were some of the Chicago painters. He had a feeling, you know, that Chicago was sort of the middle of this country, and they had a sort of a — oh, a sort of a Mexican-inspired renaissance of mural painting in Chicago doing frescos and so on and so on, and I think that he felt that it was a healthy and growing sort of thing. Since the work was, as I said, representational and more popular this would probably have a great impact, but he didn’t say that we had to be aware of this, or that we had to concern ourselves with this. He was expressing a personal enthusiasm, a personal belief and, as I said, we argued it, or denied it, or whatever, but there was no pressure exerted on us under him. As I said, I believe the man is essentially intelligent enough not to. First, he was aesthetically aware enough not to want to impose his will, which is the most important thing perhaps. As a politician, he was aware of the fact that he couldn’t direct these things completely and that some way or other a happy medium had to be found between the desire of an artist to do a good thing, a fine thing, and the thing that people would ask for. Believe me, it’s a very precarious sort of thing. Under the circumstances, why, as I said, the wolves are all around howling. If it wasn’t somebody from the extreme left, it was somebody from the extreme right, or if it wasn’t them, it was a neurotic old maid, or something else, you know, setting up a storm about something — well, just, say, obscenity of artists in general. You’d be surprised at the idea, you know, artists being let loose in a school where children were attending school. This had unsalutary features.

Well, you know, there was no precedent for this really. There wasn’t any precedent for setting up and floating this idea and making it walk. How you really go about doing it, you know. You’re bound to step on toes you didn’t even know were there…

That’s true.

Sure. Quite apart from the political interest of certain newspapers, the Mirror, the Journal-American, others who were anti-Administration and were using the Art Project as an indication of wastage and so on, you know. They were selling a wholly different idea. The only difficulty is they put theirs out in a huge paper, and you couldn’t compete on those terms. You still had to deal with the principal, the Board of Education, etc. etc., who themselves, I think, showed a rather large antipathy with that kind of pressure, don’t you?

Yes.

That there would be a public spirit or whatever it is, this feeling of necessity even operated on Boards of Education where they could see the needs of this in human terms and at the same time aesthetic terms for the school and within those limits allow employment which but for this process would not exist at all. So I think, you know, in a way they deserve a kind of nod for not being sensitive to the…

I think they deserve that because they were in a delicate position in relation to the running of the schools where even a penny spent on something that wasn’t an absolute necessity could be challenged.

Sure.

And also if an idea were to be put on a wall, I think we were in a period then of the beginning of probably one of the most difficult periods in America as far as thinking was concerned. Thinking was becoming dangerous as such. They themselves were timid about jeopardizing their own careers because after all, maybe these people, these artists, do these things, do you see what I mean?

Sure.

Don’t forget this was a period of great fear from the Dies Committee and McCarthy and so on. That’s why these organizations gained such power in repudiating the work of a man, or something of the sort, because of suspected association, or whatever else it may be. It’s like the murals that were condemned — like one mural torn down off the wall, as I said, absolutely unjustified as far as a careful analysis of the work was concerned — simply because somebody saw a Red Star and so on and carried it back to his American Legion Post, got the Post up in arms about it, and made such a furor that they ordered the thing torn down. Now, it was groundless, but the action took place so fast. I think that what happened there probably could be, I think, typified in a situation where you had the Post demand that a certain mural be stopped and taken down in another high school. I just couldn’t see any reason, but this man came to the project with a committee from the Post. He was extremely vocal. The other two men just sort of sat there. I have the feeling that he came bearing the Post’s authority, of the veterans, you see, so you had to listen, and I listened very carefully. I brought out some photographs to speak to him about it, you know, to indicate “What? Will you please tell?” The charges he made were so ludicrous it was funny! I said then that the only thing I could do would be to take it into consideration, to take it up with some other people, and I said, “If possible, your Post. Nothing would be done very quickly.” By that I meant nothing was going to be done that would matter, if we didn’t come to a decision within two or three days, or a week or whatever. So a couple of days later I went to the Post. I went in, and I met the commander of the post who happened to be a very innocent sort of person. I told him who I was, and I told him what had happened. I had photographs and things there, and I asked him, I said, “Do you know this man carries the authority of your post? Do you know what he said?” He said, “Oh, yes. He said so and so and so and so.” I said, “Fine. You do know that. Do you know what he means when he says that? Have you looked, have you checked?” “Well, no. After all, that man is perfectly competent.” I said, “Is he? Let’s just get together here. Here’s some material.” Finally he called a couple of other officers over. They went over the material. When they got through, they were so disgusted and embarrassed, and finally he said to me, “Look, I’m terribly sorry. That guy’s a pain in the neck anyway. He’s always off screaming about something.” I said, “Well, it’s a fine place to put him on the Americanization Committee in times like this, in difficulties like this, and then have him carry the authority of your Post.” The result was I never saw or heard from the little man again.

That’s interesting. In the mural field what kind of pressure did you get from the Society of American Mural Painters, which, I think, is a New York City organization.

Oh, I think the Society of Mural Painters — after all, they had pretty much control of all the big murals that were being given out in the State buildings and for City buildings and so on and so on, and they had things so thoroughly tied up. I think they were so infinitely superior to us they didn’t give a damn.

They didn’t care.

I think that they really cared, but they wouldn’t lower themselves. I think there were a few contacts here and there, because, after all, a lot of their people were becoming unemployed. But I’m sure that in a sense though, as a group, probably the controlling group of it were as anti-WPA as anybody else was that were successful business people.

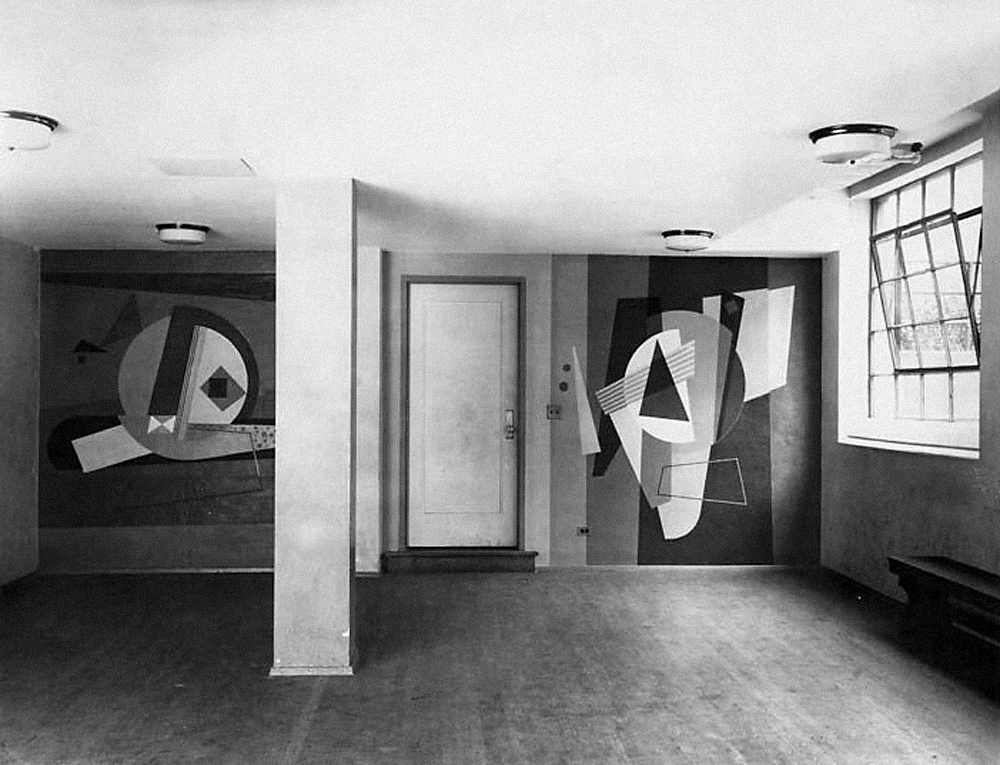

Yes. Yes. You mentioned the name of an architect before who ought to go in here somewhere as one of those who aided and abetted the development of the abstract, and that’s Lescaze.

Yes. That was in the early days, the very early days of the project, and when I had assigned certain artists as assistants to other artists with whom they would be most compatible, we still had the problem of finding places for more abstract paintings, and Lescaze, Rene Lescaze, was the architect for the Williamsburg housing project. We got together at one point, and I told him that I thought that we had some fine abstract painters and they should have walls to work on. It stuck at the time in pictures and scenes in history that the rooms they would be working in would be playrooms and general public areas that would be so informal rather, and limited really in space and without the housing project having a personal theme that they wanted to foster, we could probably have these abstract painters do things that would be very decorative, very colorful and probably people moving into this housing project might need that touch of color and decoration around, something to give a little life and gaiety to these rather bleak buildings. There was not much that Lescaze could do in terms of decoration because all the money went into building space, you see. He was very enthusiastic about it, and he really – you could imagine from his viewpoint, he had a problem in convincing the authorities that be that this was a worthwhile project. It culminated in our having most of the men I had available at the time being assigned to jobs. It worked out quite well, except I think that — well, the exception has nothing to do with the doing, or anything of the sort, but like in those early housing projects I doubt if there is very much left of the murals that were painted. As I said, it’s pretty close quarters and a lot of people are — I think that was one of the earliest and biggest housing developments, experiments sort of, in town. The next fairly large project that came about was the — well, I had a supervisor named Yuchenko who had a very good contact with the people at WNYC, because he had been very much interested in some of the work they had been doing in the broadcasting station field. We got together a good many times. Finally I managed, without too much difficulty, to convince Novak and others there, who were quite excited about the idea, of having more contemporary works in the broadcasting studios, that it would be more fitting, and so on. Of course, don’t forget, it’s a city institution and even in WNYC, you did not go down and paint murals. The station had to request the murals, that went to the architects for the City and then that went to the — well, I think it came under the Commissioner of Docks at the time. I believe it’s the Commissioner of Docks, so it had to go to him for approval. Then he had to submit it to the New York City Art Commission and they gave you permission to begin, as I told you before in the case of schools, and then back down again. So, again, it wasn’t foisting abstract work down the public’s throat either…

No.

It still had to go through the City itself and the City departments and the New York City Art Commission. But you know there was an extraordinary man on that New York City Art Commission that did an awful lot in many ways for the art programs. His name was Ernest Pachano. He was a remarkable man. He was a very, very academic painter, who did murals in several banks in New York City and so on, and he was then way in his 70s. He was in his 70s then, but I had to pick him up and take him around to these mural projects periodically, every couple of weeks or so, or every week, or whatever time he could possibly take off, and he’d view them for the Art Commission. To show you in a way what type of person he was. One day there were five murals I wanted him to view because they were getting along, and he was supposed to see the different stages of work. One of them was Phil Guston; another was Brooks, James Brooks; another was Seymour Fogel; and there were a couple of others. Well, you know, we went up where the artists lived, of course in a very shabby loft you know, in a shabby building on a shabby street. This is what they could afford, or they couldn’t afford it, but somehow or other they managed it, so we’d trudge up these winding staircases to get up to the loft and view the work and talk with the artist. Then back down, and we’d get in the car and go on to the next one. We went to three of them. Finally Pachano said, “Mr. Diller, do you mind? I don’t feel well. Would you mind if we went back to my house instead of seeing the other two things today?” I said, “No, not at all.” Well at his age, and he did, he looked ill, you know, I was very concerned about his health. “For heaven’s sake, why didn’t you tell me before!” “No, no, no,” he said, “let’s get in and go back to my house.” We drove up to his house which was in the 70s, and he invited me up and he asked the maid he had to bring in a rare bottle of brandy. It was very ceremoniously poured, and he sat there sniffing it. After a little bit he said, “You know I feel much better now.” “Do you know why I felt sick? You know when I was a young man I had a mediocre talent. I learned technically how to do this kind of illustration. For a very mediocre talent I lived a beautiful life. I got well paid, more than well paid for anything and everything I ever did. I have met wonderful people. I have had enough money to associate with them, to do things nicely, but today, just as many days as I’ve gone out with you, I’ve gone up into the dirtiest holes in the wall to see the work of young artists. I’d see one. Then I saw two. Then I saw three and I never had the talent that they’ve got in their fingertips, and here they are living on absolute marginal living. They don’t know where the next meal is coming from, practically no possibility in the world of having a job, you know, of using their work. It’s enough to make me feel absolutely sick at my stomach. Now this is a tremendous person who could say something like that and mean it. He was extremely helpful in the Art Commission because at the time the Mayor was designating the Art Commissioner and the other appointees — you know, there was a sculptor member, a painter member, an architect, and so on and so on. The result was that they were rather academic people and some of them represented the good societies – art, mural, sculpture societies in New York. They were just not too concerned about the kind of work that these young people were doing, but he was a very strong force in his quiet little way.

I know that in WNYC, for example, Davis has a mural…

That’s right.

You know, and it’s in his tradition. Getting that accepted, you know, the request that comes from the Station and spins up that stream of possible veto power. It took persuasion and at least, you know, another eye or a different sense than the traditional one even to entertain the possibility of a Davis mural in the Radio Station. I don’t know whether it created any fuss, or not. Davis himself didn’t say, except that it is one of his murals, but I can see the difficulty which you as a person who had to go out and get sponsorship, or enlist sponsorship, would confront. With your own interest in the more modern, abstract paintings, having a fellow like Pachano was…

Well, I think there were — you see, again, there were just enough people around like Commissioner McKenzie who was Commissioner of Docks. Dealing with a man like that — it was a pleasure. Here’s a man whose whole background as far as art activities, or interest were concerned was rather pedestrian, but I mean a man, an extremely intelligent person, who was well aware that there were many worlds that he wasn’t an authority on because he happened to be Commissioner of Docks, or something of the sort. The result was, I feel, that if he believed you were a sound person, were honest, and if he considered you were expert in your field, he would grant you the benefit of the doubt and be willing to support it. I give you a very, very good case of this. Ferdinand Leger wanted to paint — above all wanted to have a mural in America. He’d never had one in Europe, and they thought there was a wonderful possibility of his doing something in America. No one at the time seemed to take it upon themselves — private industry or anything of the sort, you know, or whatever. The corporations didn’t have the interest they have now in these things, because, you know, they’re assets now because they’re pretty good advertising, pretty cheap advertising …

Yes.

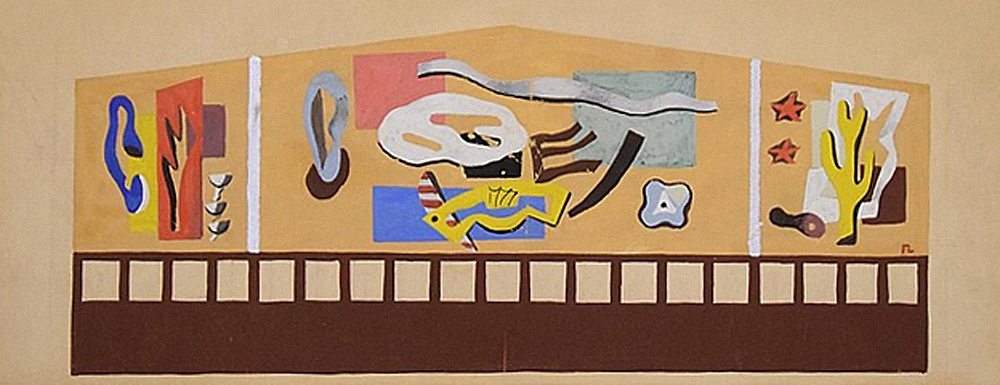

So that Leger apparently was unable to obtain that thing, but through discussions with James Johnson Sweeney, who was then at the Modern Museum, and Bonnet. There was a Miss Bonnet who had some liaison with the French Government – had contact – Therese Bonnet, I think, and one or two others. They got in contact with the Project as a possibility, so that after their discussions with Audrey McMahon, who thoroughly approved of the idea that something might be done on the Project, it was turned over to me to see if it would be possible. You see, we couldn’t employ him as an artist on the Project either as relief, or non-relief because he was not a citizen. But on the other hand we’d have an excuse for using him because of his name and so on, and the fact that a good many American artists might like to work with him on a mural, you see, so it would give them employment. We decided that it would work if we could find a place where we could do a job that would employ a group of American artists that might take the same theme that he would take. In other words, if there were enough panels or positions for murals, that he could collaborate with them, and he could more or less establish a theme and then they could do whatever variations on that theme that they pleased, you see. It might make an extremely interesting project. Well, it was so exciting to all of us, you know, to do it, and dealing with Leger was a very great pleasure, and we got a group of artists to work with him. He came down to the studio area we had at the time, office and studio area. He worked with these artists.

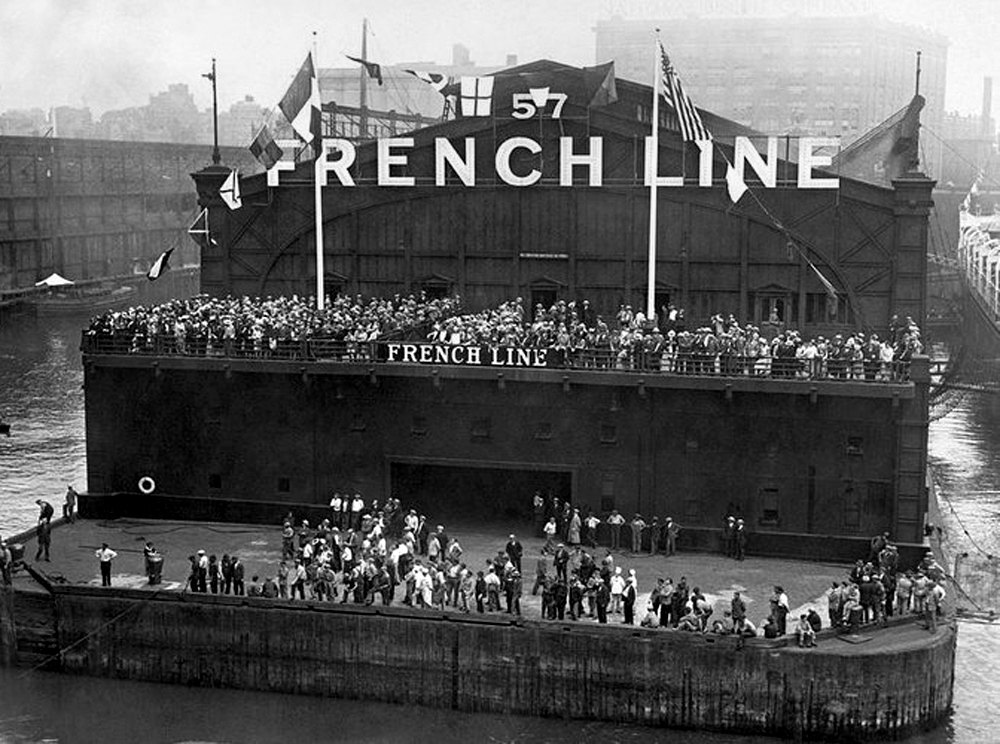

Then he drew lots at his own studio, the place where he was staying, until finally we developed this series of sketches for this mural for a position, a place that had been suggested somewhere along the line, that maybe the French Line pier would be good. Well, it was a natural, you know, for Leger to do in collaboration with American artists, to do decorations for the French Line pier. Then a Monsieur de l’Enclet was contacted, who was head of the French Steamship Lines. The reason he had to be contacted was because they would have to be sponsors, because they were leasing the pier from the City of New York, but we could do the work in the pier if it became a permanent part of the pier, do you see? Because it was a city-owned structure. Again it looked — a Frenchman you know and so on, that a man like that would certainly be very excited. Mr. de l’Enclet was as cold and non-committal as a man could be in all the preliminary work. When we had all of the work finished finally, we got to the presentation sketches. I made an appointment at de l’Enclet’s office for Leger and myself to come up and show them the preliminary sketches, which could be submitted by him then to the Art Commission, or the Commissioner of Docks rather and then to the Art Commission.

I had already shown them to the Commissioner of Docks, and he had gone along with it. He said, “Well they certainly are going to be bright and cheerful. I think it would be a wonderful thing to have in the pier.” As I said, he wasn’t concerned about their being abstract paintings or any other sort, because they were sea forms that were rather developed, you know, of all the motifs that Leger had established. Well, I brought the sketches with Leger. I went with Leger to de l’Enclet’s office. After cooling our heels for at least three quarters of an hour, we were finally admitted to the royal presence. I introduced Mr. de l’Enclet to Leger, and he said, “I know that man,” and he started off a tirade in French. I was able to read a bit of French. I could understand it, you know, to a certain extent if you spoke carefully, but this was a torrent. I could get enough of the conversation to know what was going on. Then Leger pops up, and he starts. De l’Enclet had practically told him, “Well, you damn worker, you! You communist!” And so on and so on, and he really insulted Leger to no end. Leger naturally was terrifically indignant about the thing, and so I finally walked over and picked up the sketches, and I said, “Well, Mr. de l’Enclet, thanks for your French courtesy!” I said, “Leger, I don’t think there is any reason to stay here any longer.” We picked up and walked out. That was the end of that project. Yes, you got involved in some funny things in the project days, some extraordinary people.

Sure. What a strange kind of a mess that was. Tell me, so far as the New York office itself was concerned, I mean apart from you as a supervisor, a field man, an inspector, in a way, how much rationale did the Project obtain locally in New York from its own leader, Mrs. McMahon?

You mean in terms of aesthetic direction?

Direction, yes.

Mrs. McMahon was extremely broad in her viewpoint. I think that she only concurred with Cahill in the attitude in the beginning that they had to be wary of trying to introduce certain abstract forms and so on because it might militate against the employment. But on the other hand, when I did start to place people she certainly went along with it and would have supported me in doing it because she didn’t object certainly not to the idea of the work. She was rather glad it could be done. You see, as the thing developed and there were so many murals going on, as I said, if you take a ratio of one out of ten, or one out of twenty, who is going to criticize it, because they’re still valid works. They could be called decoration, if nothing else. They didn’t have to be called art or anything — you know, abstract or anything. So you know the name was a dangerous thing. I found in other places that we introduced abstract work just simply by calling it, talking to their committees about the decoration, if you avoided the word “art”, they were very happy.

I’ll be darned.

Of course, if you introduced the word art then you were in for it, you see!

Yes. Then I suspect that her problem…

In other words they were people that didn’t know anything about art, but they knew what they liked. But on the other hand they were much freer in their choice of decoration.

Yes. Well, that’s a subjective thing anyway. Well, I suspect in terms of what you initially said that you had so much funds allotted and those funds had to be spent for salaries for unemployed artists that could be employed on a public project.

That’s right.

The more projects you had, the happier she would be in the sense of maintaining the flow of funds which had been made available, an administrative problem as distinct from a selective one as to whether they should be square, or round, or circular, or otherwise. She let that go.

That’s right. She didn’t let it go. She was interested. She was concerned with it, but she didn’t use authority to try to dictate it in any fashion. I mean there were things that were done. On the other hand, which she considered were rottenly academic. As works of art she considered them nothing, but on the other hand, they were in places where those people wanted those things and they performed a certain kind of function.

Yes.

And so as a matter of fact, if you just thought well they’re illustrations for these people and for this particular group, and so on — again, it’s like calling abstract art just decoration. Call the other — well, it’s just illustration, and let it go at that. Why argue about it’s being art? Although, as I said, she was thoroughly upset a few times. She thought the thing was getting too trite and so on. She had a real concern about it.

Yes. Which is good.

What’s that?

Which is good; namely, you have a sympathetic response for a program and its consequence, which is what she had.

Well, I think you had a person there that was more concerned about art, and about the artist and while she herself could function in the political sense, or administrative sense and political sense and she did, her main concern I think, after all, was being editor of Parnassus you know, the College Art Magazine, being associated with that, and in the past had been connected with other social and art activities. But she was very well-equipped for that sort of thing and had so much more than a straight administrative person without technical knowledge, or insight into what the problem of the artist might be.

Yes.

You see, it took understanding. We had this demand from outside to have time clocks and also at one point a demand to have the artists work in studios on the premises. Well, this is ridiculous. An artist might have a shabby little room, a dirty little room, but he’s pinned some things on the wall, and he lives there, and it’s his environment, and this is what he works from. But to bring him in to a commercial building and give him a little section in the corner and say, “Now paint from nine to four,” or something of the sort! Yet this is the thing that they were constantly trying to impose upon us. Now the time-keeping things. She had under her administration, of course, your purely administrative personnel, I mean the man who took care of the business. You had the man who took care of the time-keeping, your time-keeping division, and so on; and you had your other technical divisions. Under these were the actual division related to the art. She had to be the intermediary within her own department and above, you see, correlate these things, because if a timekeeper came in and said, “I found so and so asleep,” — when they insisted on having the timekeepers check easel painters — “I went there five days and he was sound asleep at three o’clock in the afternoon.” The timekeeper’s recommendation was that he be dismissed, you see. Then possibly they’d get thoroughly upset and go up to administrative headquarters and try to get their authority to wield a bigger stick about these artists that were sloughing off. Well, of course, somehow or other it invariably happened that the artist who was asleep at three o’clock on the five days he called there was a guy who works all night, and who probably was one of the best painters we had on the project. Now I could understand it. In my own case I know damn well I might be asleep at three o’clock. Maybe I worked till six in the morning if I was painting at that particular time. I did. I painted half the night — you know, when you get through with this other sort of business. But she had to understand this, too. The only way you could understand it was to know the artists personally, and to know his aims, what his limitations were, understand him as a human being, which purely administratively isn’t being done in any organization; however, it’s necessary.

I wondered what her relationship was to the over-all…

Am I getting shrill. With this damn tape here you find yourself talking —-

I don’t know.

Or is it just…?

It’s fun. You’ve got some good insight into it, too, as you would necessarily have, having gone through the experience. It’s rubbed off. It’s in you. And, as I think you pointed out, this is a period which you haven’t seen since, nor did it exist before. Just this kind of flavor. Understanding, for one thing. But there was introduced, I think, in New York — well the first man was Iron Pants Johnson, wasn’t he?

Oh! Yes. Hugh Johnson.

Yes. Who at that particular time had been having not a few personal difficulties on the national scene. But he was followed by a military figure, an engineer.

Brean Somerville.

Who in his own field is, you know, second to none, but here in this particular instance he had a pretty bad press, a pretty bad press in the sense that his announcements seemed to be highly arbitrary, namely, you were going to pare down the lists of artists by some thirty percent cut…

That’s right.

Now he may have been under instructions from Washington…

Somerville — I think I had some understanding of the man in a way, the man, because of the past. The attitude that the general WPA administration had, that side of it, with Hugh Johnson and then followed by Somerville, but mainly generated through Johnson’s offices was that the Art Programs on the whole were hotbeds of Communist activity, that they really were impediments to the WPA administration in their bigger programs, because all of the scare heads came from the art programs.

I see.

And don’t forget that your art programs — the theater, and writing, and music, and art — these are the things people write about. No matter what is going on in the other programs, who heard of it?

Yes.